Dissertation Framework

Table of Contents

- Critical fandoms.

- Defining Ideology.

- Why examine critical fandoms through an RGS lens?

- Why feminist digital humanities?

This project uses an interdisciplinary framework. I examine fanfiction genres and critical fan composing practices through critical fan studies and rhetorical genre studies (RGS) lenses. I also rely on feminist digital humanities (DH) to make decisions around methods, data transformation, and publication choices. Visit this project's ongoing bibligraphy page for citation information

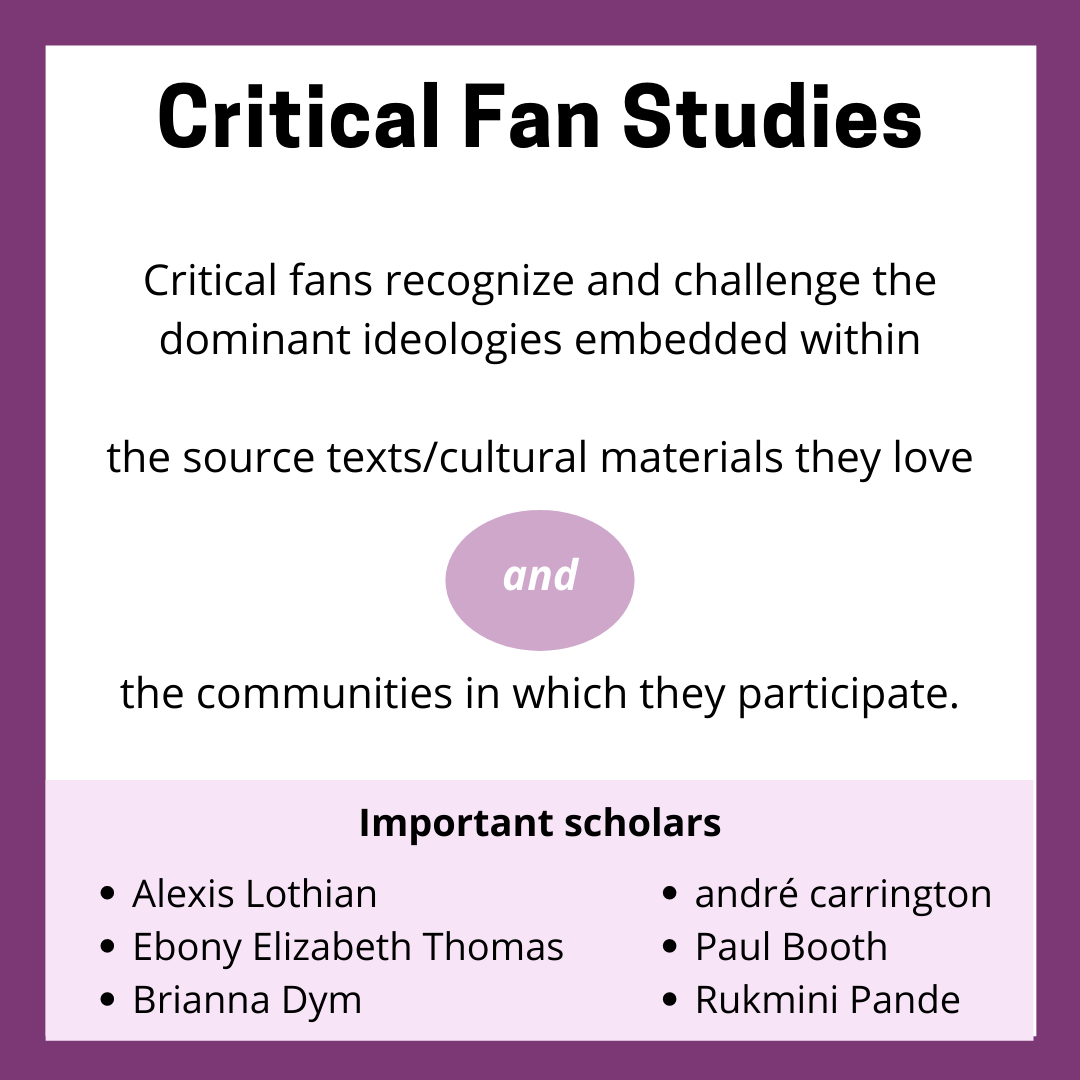

Critical Fandoms

As Paulo Freire defines in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, critical consciousness is the exploration of and resistance to systems of power and oppression that permeate social and political norms. The definition of “critical fandom” carries Freire’s ideas to fanfiction and fan genres, particularly when thinking about the exclusive cultural ideologies reinforced and embedded in original cultural materials. Paul Booth (2015) calls for a shift in how academic fans write about fan studies, specifically shifting away from trying to place a neoliberal “value” on critical fan practices and instead acknowledging the work — often unpaid and resistant to neoliberal notions of intellectual property and ownership — already being done in fandoms.

Booth emphasizes that fans are often doing critical work in their everyday practices. Fandoms are, as Booth argues, “the classroom of the future” in which academics need to listen to the critical work already being done in fandoms and value these frameworks in our research. Booth’s article demonstrates fan scholars’ investments in amplifying fans’ voices; scholars who analyze fandoms must also listen to the work being done by fans.

andré carrington (2013) also argues that fanfiction is “critical reception,” or how fans challenge hegemonic and harmful mainstream narratives in their practices. Specifically, carrington highlights Black fans writing about Black characters or racebending characters to better represent their own experiences. “Critical reception” prioritizes how fans, especially Black fans, always-already recognize and challenge the misrepresentations or erasures of particular people and stories in mainstream media. Abigail De Kosnik and carrington (2019) continue focusing on fans of color and critical race theory in the special issue “Fans of Color, Fandoms of Color” in Transformative Works and Cultures, addressing how fandoms and fans of color have been largely ignored by fan scholars, demonstrating how the white supremacy we often critique in media exists in our own discipline.

Alexis Lothian’s definition of “critical fandom” continues carrington’s and Booth’s work by defining how fan practices can be critical (or not): “critical fandoms [are] the ways that members of fan communities use diverse creative techniques to challenge the structures and representations around which their communities are organized” (Lothian 2018, p. 372). Lothian’s definition partially comes from Paul Booth’s (2012) call for academics to both “listen to fandom; and it is our responsibility as fans to promote critical fandom in all our work” (emphasis mine). Critical fan studies, then, prioritize fan practices that actively challenge white supremacy, gender inequality, heteronormativity, and ableism in the source texts, fandoms, and fan studies.

Defining Ideology

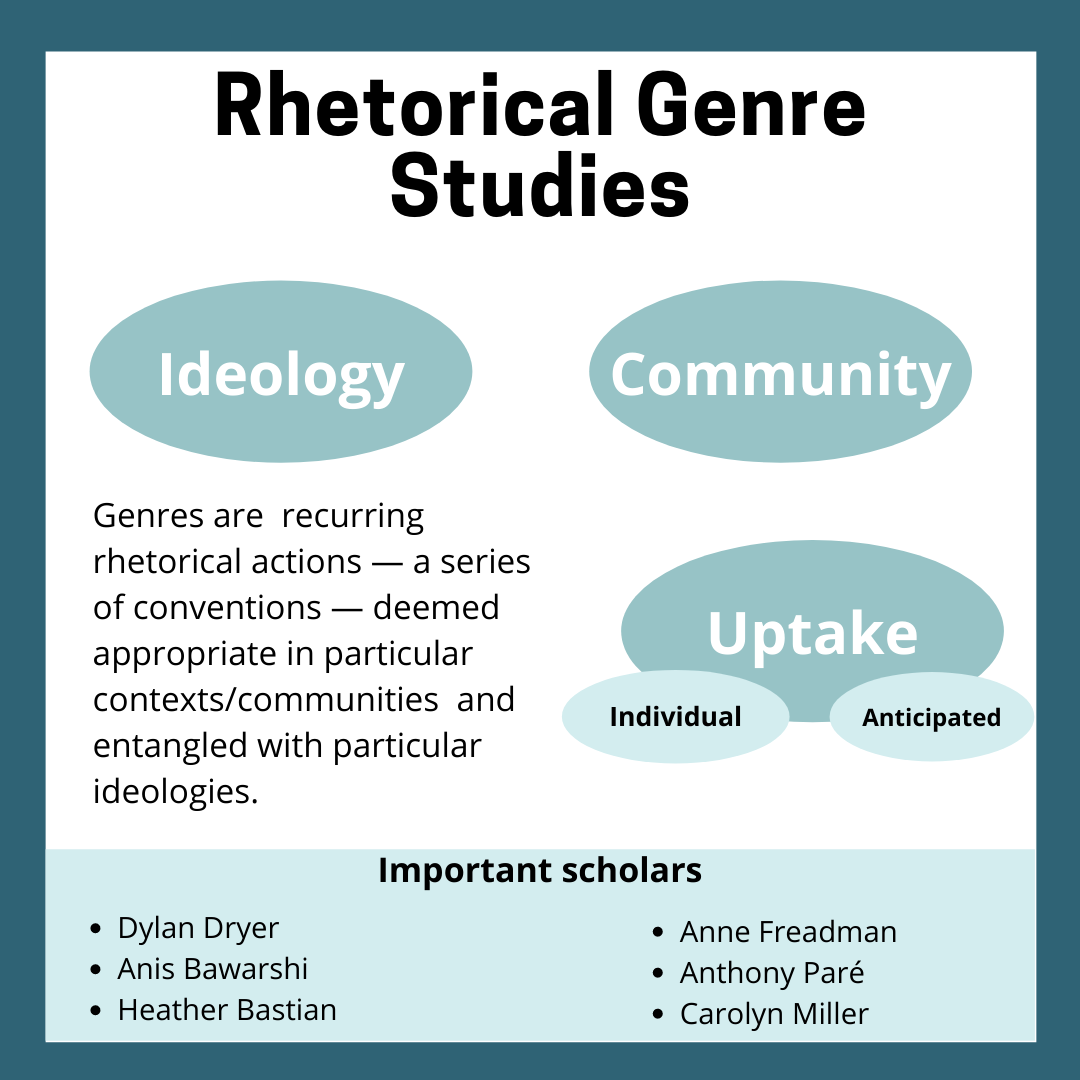

Ideology has a long, complicated history of conflicting definitions. This project defines ideology through the lens of social construction and rhetorical genre studies. Ideology is philosophical and political beliefs that encompass notions of citizenship, identity, and power as well as how these beliefs are enacted, reinscribed, or challenged through policy, culture, and everyday individual subject’s actions. Paré defines ideology as a “a process, a socially organized activity, as the daily practices of a society’s cultural, economic, and political institutions—practices that favor a dominant minority” (p 58). Dominant ideologies are almost always harmful towards marginalized groups of people.

Paré’s definition brings several important aspects of ideology. First, ideology is a “socially organized” process, implying it is ever-fluctuating, contextualized, recurring, and social. Second, ideology is about power, especially how power is replicated and reified across institutions (cultural, economic, political, and educational). Finally, ideology is about “daily practices,” in that our everyday acts can uphold these ideologies. Dominant ideologies are pervasive on a systemic, community, and individual levels. Examples of dominant ideologies include heteronormativity, white supremacy, and ableism.

Why examine critical fandoms through an RGS lens?

Since the 1980s, fan studies scholars have celebrated the modes of resistance fan writers take up as they produce and read fan texts as well as create publics in which these texts circulate (Russ, 1985; Lamb & Veith, 1986; Jenkins, 1992). Scholars in writing studies and rhetoric have studied fan communities to explore writing development (Roozen, 2009; Black, 2008 & 2009), fans’ negotiations of their politics and the politics represented in the source texts they love (Summers, 2010), fanfiction as a remix literacy (Stedman, 2012), and the ways in which fans produce and contribute to reimagining the original cultural materials (Potts, 2015; DeLuca, 2018).

Roozen (2009) examines one writers’ vernacular and discursive shifts in participating both academic and fan literacies. Summers (2010) traces how fans in a Twilight discussion board negotiate their feminist identities while analyzing a text that some read as anti-feminist. DeLuca (2018) argues for the importance of bringing fan composing practices into the classroom, as they center affect and teach transferable composing skills. Yet, compared to the vast amount of work on cultural impacts of fandoms, pedagogical implications, literacies, and genres of fanfiction and fan communities as well as the intersection with writers’ identities and knowledge-making practices are still understudied.

To research fanfiction means recognizing fanfiction writing practices that are defined by fans’ everyday practices, politics, and interactions. Charles Bazerman (2016) defines writing as “a social technology designed to communicate among people. It is learned and produced in social circumstances, establishes social relationships, changes the writer’s social presence, creates shared meaning, and accomplishes social action” (p. 11). Bazerman’s emphasis on the social and communal nature of writing applies directly to fan writing practices, as fan writing is defined by fans. Bazerman argues that writing is “socially sponsored and shaped by the sponsor’s agendas” (p. 16); in fan communities, fans are almost always the sponsors. While writing taught in the classroom or published in journals are often more rigid in standards and expectations, fan writing is by fans, for fans, and circulated among fans. The barriers for participating in fandoms are few, and those that do exist are normally enforced by the community, rather than an external institution such as education or corporations.

Rhetorical genre studies (RGS) provides a lens for studying generic performance as part of this social process; genre conventions are created and perpetuated by fan community members’ actions, and there are ideologies embedded within these conventions. Hampton (2015) demonstrates just how fan studies, performance studies, and rhetorical genre studies can work together:

Reading fan practices as categories of performance within the cultural repertoire aligns our method of analysis with fandom's valuing of embodied knowledge and lived experience and its ephemerality. Fandom's use of the same characters in repeated tropes—such as first-time, hurt/comfort, or friends-to-lovers—does, at least in literary terms, make it easy to discuss fan fiction produced through generic conventions and formulas.

This moment from Hampton’s piece is important for the CFT because Hampton shows how different tropes — or genre conventions – are performances that are rhetorical, situational, and recurrent. Performance studies and RGS situate action as ideological, rhetorical, and recurrent within particular contexts. As writers perform genres, they are also performing particular aspects of their identities, simultaneously navigating or critiquing dominant, oppressive ideologies while offering a transformative reimagining of systems of power.

I am explicitly interested in thinking about fanfiction as uptake, or the anticipated generic responses to another genre (Freadman, 1994 & 2002; Bawarshi, 200 & 2006; Bastian, 2015; Dryer, 2016; Messina, 2019). I build off Bastian’s (2015) methodology of individual uptakes. She argues uptakes are often a “rigid force” and a “habitual and unconscious process.” For instance, replying to a wedding invitation by checking off “Going” on an RSVP card and filling in your name may feel like second nature. Focusing on individual uptake, then, provides methods for RGS scholars “to account for the intentions and designs that people bring to uptake.” Specifically, by naming and defining uptake, and then examining individuals’ choices while they uptake can reveal how the “habitual nature of uptake” reify dominant ideologies as well as how individuals resist these ideologies in their choices.

I also incorporate Dryer’s (2016) uptake taxonomy; I specifically use “uptake enactments,” or the actual action of the uptake, and “uptake artifacts,” or the material product. Tracing fans’ uptakes, both uptake enactment — the fans’ process of writing fanfiction — and uptake artifacts — the actual fanfiction — provides a method for better defining:

- fanfiction genre conventions,

- how these conventions are defined by fan communities,

- how individual fans interpret and uptake these conventions,

- the ideologies embedded in these conventions,

- and how these conventions can either be challenged or reinforced through individual fan composers’ everyday uptakes.

Why Feminist Digital Humanities (DH)?

DH is an interdisciplinary field in which scholars apply humanistic lenses to digital spaces, including social media platforms, information systems, and communication technologies. I am purposefully keeping my definition of DH broad, as DH can even extend past the humanities, helping to inform disciplines in the Social Sciences and Library & Information Systems (LIS). DH appears in rhetoric and writing studies in several academic spaces, including the peer-reviewed journals Kairos and Computers and Composition and at annual conferences like “Computers and Writing.”

I specifically emphasize feminist DH, a sub-field that is committed to feminist praxis — especially anti-racist and queer feminism — interwoven with DH methods and methodologies (Wernimont, 2015; Bailey, 2015; Bailey et. al, 2016; Losh & Wernimont, 2018; Lothian, 2018; D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

Bringing digital humanities into this dissertation helps me understand several important components, especially since this project is open-access and works with qualitative, quantitatie, and textual data.

- models for digital publishing (Arola, Ball, & Sheppard, 2014; Visconti, 2015; Eyman et. al, 2016),

- computational research methods (Programming Historian; Klein, 2020; Quinn, 2020),

- how knowledge, information, and data is constructed, analyzed, and modeled (Flanders, 2009; Bardzell, 2010; Fiesler, 2016; ; Rawson & Muñoz, 2016; Losh & Wernimont, 2018; Levesque DeCamp, 2020; D'Ignazio & Klein, 2020; Ahnert et. al, 2020),

- how this knowledge perpetuates or subverts dominant ideologies (Bailey, 2015; Posner, 2016; Losh & Wernimont, 2018; Levesque Decamp, 2020; D'Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

With all this in mind, merging fan studies and DH is important because now fan communities are often developed in digital spaces. This project relies on the theoretical and disciplinary groundwork for best ethical research practices, understanding how information systems can reify or subvert dominant ideologies, and methods for analyzing digital data. Visit the "Methods" and the "Research Ethics and Positionality" portions of the CFT to learn how I integrate feminist DH.